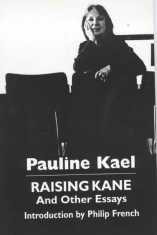

Raising Kane (excerpts)

(click image for a link to the full essay, excerpts organized by page number)

(4)

(4)The mechanics of movies are rarely as entertaining as they are in Citizen Kane, as cleverly designed to be the kind of fun that keeps one alert and conscious of the enjoyment of the artifices themselves.

Citizen Kane is made up of an astonishing number of such bits of technique, and of sequences built to make their points and get their laughs and hit climax just before a fast cut takes us to the next. It is practically a collection of blackout sketches, but blackout sketches arranged to comment on each other, and it was planned that way right in the shooting script.

It is difficult to explain what makes any great work, and particularly difficult with movies, and maybe more so with Citizen Kane than with other great movies, because it isn’t a work of special depth or a work of subtle beauty. It is a shallow work, a shallow masterpiece. Those who try to account for its stature as a film by claiming it to be profound are simply dodging the problem - or maybe they don’t recognize that there is one.

(15)

One couldn’t really call a colloquial, skeptical comedy a “masterpiece,” as one could sometimes call a silent comedy a masterpiece, especially if the talkie looked quite banal and was so topical it felt transient. But I think that many of us enjoyed these comedies more, even though we may not have felt very secure about the aesthetic ground for our enjoyment. The talking comedies weren’t as aesthetically pure as the silents, yet they felt liberating in a way that even great silents didn’t. The elements to which we could respond were multiplied; now there were vocal nuances, new kinds of timing, and wonderful new tricks, like the infectious way Claudette Colbert used to break up while listening to someone. It’s easy to see why Europeans, who couldn’t follow the slang and the jokes and didn’t understand the whole satirical frame of reference, should prefer our actions films and Westerns. But it’s a bad joke on our good jokes that film enthusiasts here often take their cues on the American movie past from Europe, and so they ignore the tradition of comic irreverences and become connoisseurs of the “visuals” and “mises en scene” of action pictures, which are usually too silly even to be called reactionary. They’re sub-reactionary - the antique melodramas of silent days with noise added - a mass art better suited, one might think, to Fascism, or even feudalism, than to democracy.

(16)

There is another reason the American talking comedies, despite their popularity, are so seldom valued highly by film aestheticians. The dream-art kind of film, which lends itself to beautiful visual imagery, is generally the creation of the “artist” director, while the astringent film is more often directed by a competent, unpretentious craftsman who can be made to look very good by a good script and can be turned into a bum by a bad script. And this competent craftsman may be too worldly and too practical to do the “imaginative” bits that sometimes helped make the reputations of “artist” directors.

The thirties, though they had their own load of sentimentality, were the hardest-headed period of American movies, and their plainness of style, with its absence of false “cultural” overtones, has never got its due aesthetically. Film students - and their teachers - often become interested in movies just because they are the kind of people who are emotionally affected by the blind-beggar bits, and they are indifferent by temperament to the emancipation of American movies in the thirties and the role that writers played in it.

It may be that for new ideas to be successful in movies, the way must be prepared by success in other media, and the audience must have grown tired of what it’s been getting be ready for something new. There are always a few people in Hollywood who are considered mad dreamers for trying to do in movies things that have already been done in other arts. But once one of them breaks through and has a hit, he’s called a genius and everybody starts copying him.

(19)

In the silents, the heroes were often simpletons. In the talkies, the heroes were to be the men who weren’t fooled, who were smart and learned their way around. The new heroes of the screen were created in the image of their authors: they were fast-talking newspaper reporters.

(25)

The thirties writers were ambivalently nostalgic about their youths as reporters, journalists, critics, or playwrights, and they glorified the hard-drinking, cynical newspaperman. They were ambivalent about Hollywood, which they savaged and satirized whenever possible.

(61)

I think that what makes Welles’ directorial style so satisfying in this movie is that we are constantly aware of the mechanics - that the pleasure Kane gives doesn’t come from illusion but comes from our enjoyment of the dexterity of the illusionists and the working of the machinery.

(62)

It is Welles’ distinctive quality as a movie director - I think it is his genius - that he never hides his cleverness, that he makes it possible for us not only to enjoy what he does but to share his enjoyment in doing it. Welles’ showmanship is right there on the surface... There is something childlike - and great, too - about his pleasure in the magic of theatre and movies. No other director in the history of movies has been so open in his delight, so eager to share with us the game of pretending, and Welles’ silly pretense of having done everything himself is just another part of the game.

Welles’ magic as a director (at this time) was that he could put his finger right on the dramatic fun of each scene... Welles also had a special magic beyond this: he could give elan to scenes that were confused in intention, so that the movie seems to go from dramatic highlight to highlight without lagging in between. There doesn’t appear to be any waste material in Kane, because he charges right through the weak spots as if they were bright, and he almost convinces you (or does convince you) that they’re shining jewels.

Until Kane’s later years, Welles, in the role, has an almost total empathy with the audience. It’s the same kind of empathy we’re likely to feel for smart kids who grin at us when they’re showing off in the school play. It’s a beautiful kind of emotional nakedness - ingenuously exposing the sheer love of playacting - that most actors lose long before they become “professional.”

(63)

Some people used to say that Welles might be a great director but he was a bad actor, and his performances wrecked his pictures. I think just the opposite - that his directing style is such an emanation of his adolescent love of theatre that his films lack a vital unifying element when he’s not in them or when he plays only a small part in them. He needs to be at the center.

(74)

The director should be in control not because he is the sole creative intelligence but because only if he is in control can he liberate and utilize the talents of his co-workers, who languish (as directors do) in studio-factory productions. The best interpretation to put on it when a director says that a movie is totally his is not that he did it all himself but that he wasn’t interfered with, that he made the choices and the ultimate decisions, that the whole thing isn’t an unhappy compromise for which no one is responsible; not that he was the sole creator but almost the reverse - that he was free to use all the best ideas offered him.

(Little, Brown and Company - Boston - Toronto, 1971)

Labels: Pauline Kael

0 Comments:

Post a Comment

<< Home